A Bicycle Saved My Life

In 1977, I was nearly killed in a motorcycle accident, riding home on a damp August evening. In the hospital, post-surgery, the doctors told me that my legs were so badly damaged in the accident that, although I would recover, I would not walk again without a cane or crutches.

In the months that followed, my prescribed rehabilitation program enabled me to slowly move from using a walker to crutches to eventually walking with the aid of two canes. I was often in pain and per the doctor’s prognosis, doubted if I would ever get any better.

One afternoon, my three-year-old daughter, Taryn, asked if I wanted to race her up the hill of our driveway to the mailbox. Though I was using two canes, I readily agreed to her challenge. But when I took off to run, I realized that I could not do it. The pain in my legs was excruciating.

It was the first time since my accident that I realized that I was disabled.

I was devastated. It was the first time since my accident that I realized that I was disabled—not so much in my legs, but in my mind. The doctors’ prognosis that I would never walk again without help had become a safety zone—something I had just accepted. This was partly because learning to walk again hurt; it was also because I was afraid of what might happen if I failed. So instead of fighting, I surrendered.

“Today, it begins. It’s not going to be easy, but I’m going to do it inch by inch.”

The incident in the driveway became a defining moment in my life. That day, I wrote in my planner: “Today, it begins. It’s not going to be easy, but I’m going to do it inch by inch.”

The goal at the beginning of my new, self-prescribed rehabilitation program was simple. I wanted to restore some flexibility, range of motion, and strength to my legs. So I rode a stationary bicycle. I put the seat up as high as it would go, because I could barely bend my legs to make a full revolution. At first I barely did two minutes before exhausting myself. I tried to extend it by a minute or two each day. After a month I did a half an hour, increasing the speed as well. After about three months, I lowered the seat and completely bent my legs.

By the fall, five months into my regimen, I was tired of being indoors. I found my old yellow Schwinn Continental in the garage covered in dust. I used the bicycle for support, pulled myself on and began to pedal. It was easier than I had remembered, mostly because I was pedaling downhill. I made it to the end of my street and still felt great. I pedaled on. I flew down another steep hill and remember feeling as if nothing could stop me. That is, of course, when I encountered my first uphill climb. Momentum from the downhill helped me get about halfway up the hill. But I did not have enough strength to get to the top. I remember saying out loud to myself, “Okay, Coles, you wanted a new challenge. Well, here’s your chance.” I turned the bike around and tried again. After half a dozen tries, I realized that I was not going to make it. Exhausted and sweaty, I got off the bike and pushed it home.

I would not be defeated.

Every day, I took out that old Schwinn and tried again. After two weeks, I finally made it up the hill.

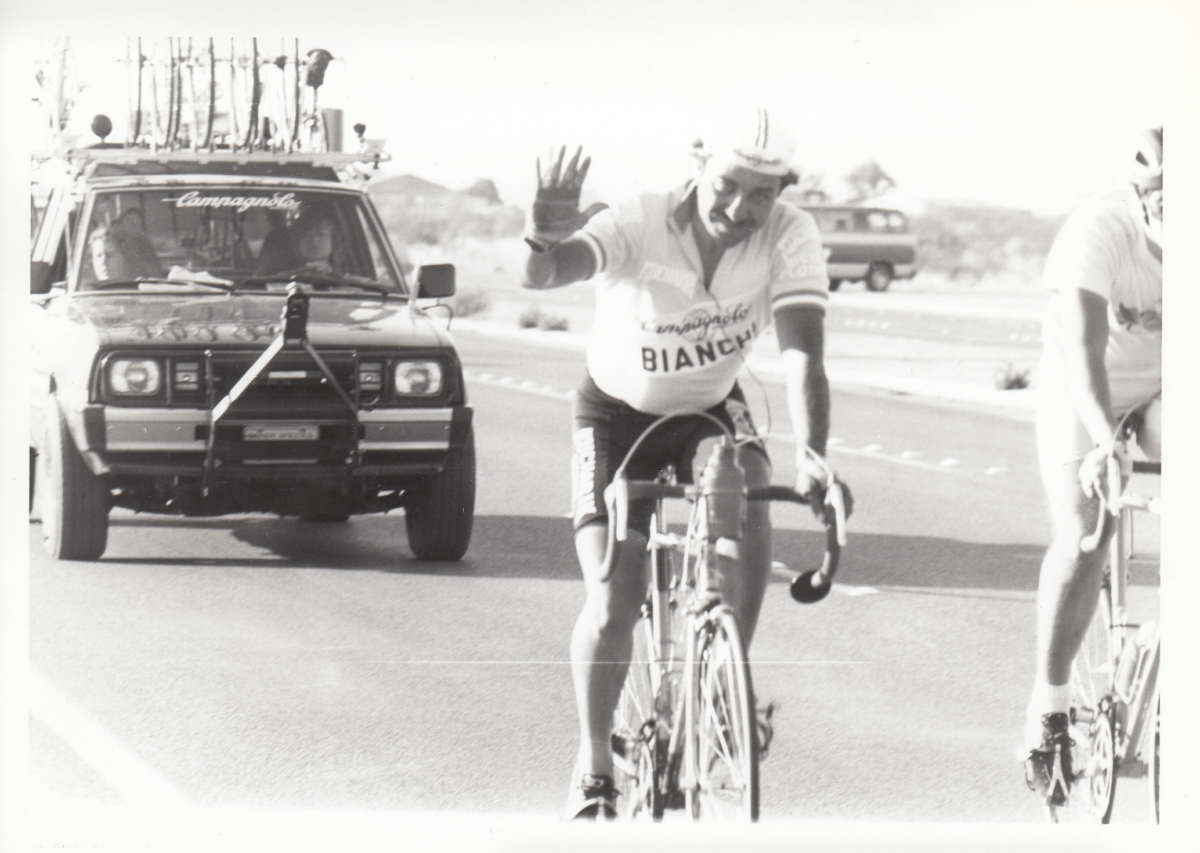

Over the next two years, I gradually increased the length of my rides, often with Taryn in a child’s seat strapped on the back. In 1982, long bike rides took on a new meaning when I broke the world record for cycling across America from Savannah to San Diego. I attempted the record again in 1983 and failed to finish the race. In a dust devil, only 488 miles from San Diego, I was blown from my bike and broke my collarbone. Again, I turned to my bicycle to support my recovery. In 1984, I broke the world record again.

A bicycle saved my life.